1903 DE DION BOUTON PARIS-MADRID

The DeDion Bouton company was famously founded in 1883 after Jules-Albert de Dion commissioned Georges Bouton and Charles Trépardoux build a toy locomotive model for him. By the turn of the century DeDion was the worlds largest automobile manufacturer and its engines were used by a multitude of other makes (some claim as many as 150).

After building Bloody Mary, I was inspired to go the opposite direction. This was motivated, as always, by the desire to tackle new challenges but also to provide a seat for our host at Gittreville who was distinctly unimpressed by our collective quest for speed.

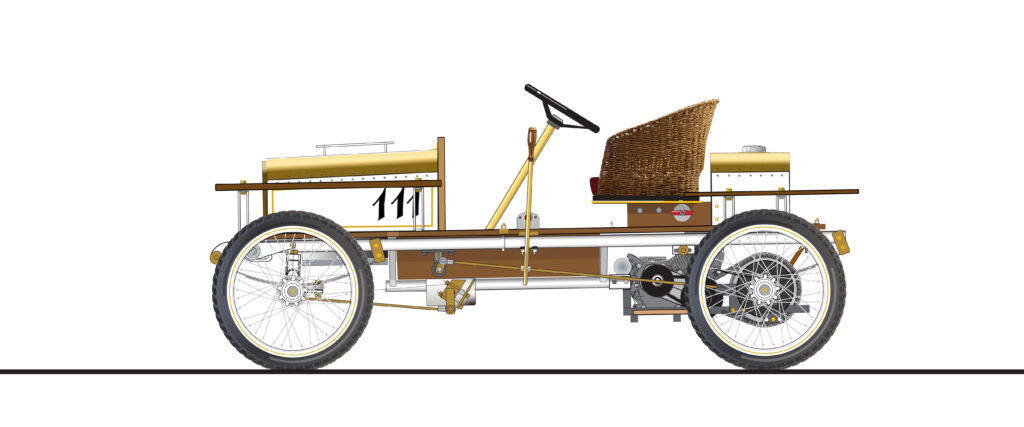

I chose the 1903 “Paris-Madrid” Type S.

The Type S was built for the infamous 1903 Paris – Madrid Race. This race was halted by the French government at Bordeaux after five drivers, including Marcel Renault, and three spectators had been killed. The debacle was the last town to town race run over public roads. The Type S also raced in the Coupe d’Ardennes later that year. The Ardennes course was one of the earliest closed courses and evolved over the century to become the track we know now as Spa.

Where Bloody Mary was simple, the DeDion was complex. Where Bloody Mary ignored conventional automobile dynamics, the DeDion embraced them. The DeDion is a much more complicated car.

Emulating its inspiration, the DeDion has a (round) tubular frame made with thin wall steel. The real strength of the chassis is the tub but unlike Bloody Mary, made with heavier, better quality oak plywood. The tub has a perimeter structure executed in solid oak. Significant portions of the body work and details are brass. Bearings are typically in cast iron carriers for period effect. The car was designed to seat two (modestly sized people) on a plush quilted leather, wicker wrapped bench. Alternately, a single “racing seat” could be installed for more spirited driving. Initially at least, the car had a massive five gallon sand rail gas tank.

All together, the complexity, the brass, the cast iron and the solid oak produced a car weighing an astonishing 305 lbs. Astonishing only to our early limited circle it turned out. Many later cars from “outside” easily bettered this.

Attention to geometry rewards the DeDion with impeccable road manners and surprisingly capable off road capabilities. In spite of a seating position best characterized as “sitting on a ladder”, the car inspires comfortable confidence.

The DeDion was never expected to “race” (it has from time to time) but rather to be a concours queen. The Marquis De Dion claimed that races of speed were useless. The only useful races in his opinion were ones of endurance and fuel efficiency. The Car debuted at Gittreville where it was driven by Madame du Coligny and her daughter Mademoiselle du Coligny; both resplendent in period fashions they designed and sewed themselves.

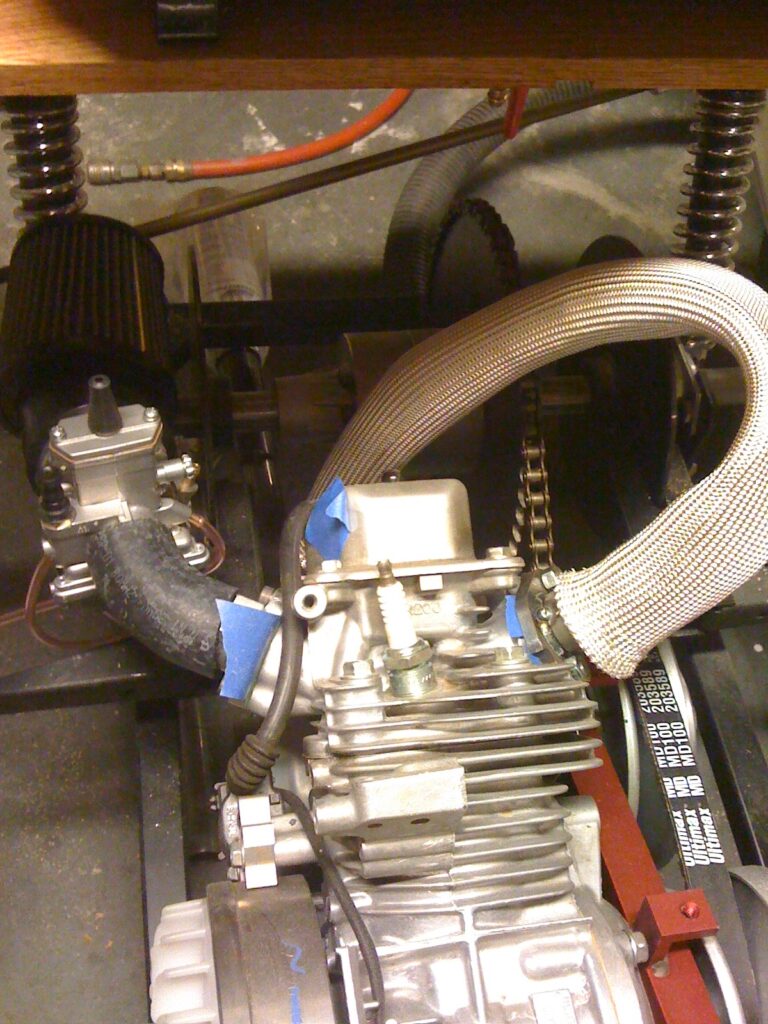

The early car had a GX200 motor tuned low and slow. A very large Mikuni was fitted on a radiator hose intake to tuck the carburetor inside the frame to allow for suspension travel at the rear. The engine mounted to a trailing sub frame with a Heim joint at the front. Both ends of the rear springs are allowed to move on compression. Lateral location is controlled by a Panhard rod. Every advantage was taken of the big Mikuni and the engine was a torque monster. The idea of having enough power for a heavy car kept the designer up at night… it needn’t have in retrospect.

The DeDion was an outlier in early cyclekart society. It tended to mostly be employed as a sedate, well mannered guest driver. She is very easy to drive and feels much more like a “real car” than a typical cyclekart does. With that role very much in mind, the car became a candidate for conversion to electric.

Electric

The gas Honda block was donated to the Chrysler which had voraciously chewed through several Predator blocks. In spite of Tuco’s ever more ambitious power milking schemes, Honda quality in the old DeDion block carries on to this day.

The geriatric electric kit from the Bugatti Tank was grafted in. It ran “a few times”. Alas, the elderly batteries were getting well past their prime and an attempt to plug in the later LiFePo batteries proved marginally compatible with the golf cart type controller. Probably something that could have been sorted out with weeks of fettling but my patience was as exhausted as the flat batteries.

Edwardian

So, the car has returned to gas. But, this time, truly stock GX200 and with electric start. No big throat Mikuni and stump pulling torque – now modest power but she’s an easy, easy, drive.

Fenders emulating the inspiration car have been fitted. More accurately, shelves masquerading as fenders — useful for drinks, appetizers, and from time to time, tools. Aluminum covers pop off the front wings to reveal marine plywood escape boards; handy for remote Edwardian trekking. What appears to be a sump has been installed under the bonnet where the bank of batteries once lived. It serves as an ice chest for Champagne.

BUILD GALLERY

It always starts with parts

It always starts with parts followed by welding

followed by welding Frame

Frame Front suspension

Front suspension

Tapping for zerk fitting

Tapping for zerk fitting Oak starts to go on

Oak starts to go on

Snug fit

Snug fit

Friction dampers

Friction dampers

Pedal set and steering column

Pedal set and steering column Bonnet on

Bonnet on

Badge engineering

Badge engineering

Bonnet hold-downs

Bonnet hold-downs First test drive – to local park

First test drive – to local park First weigh in

First weigh in Single seat

Single seat Seat weaving

Seat weaving

Wicker double seat fitted

Wicker double seat fitted Radiator screen

Radiator screen Badge filing

Badge filing Upholstery begins

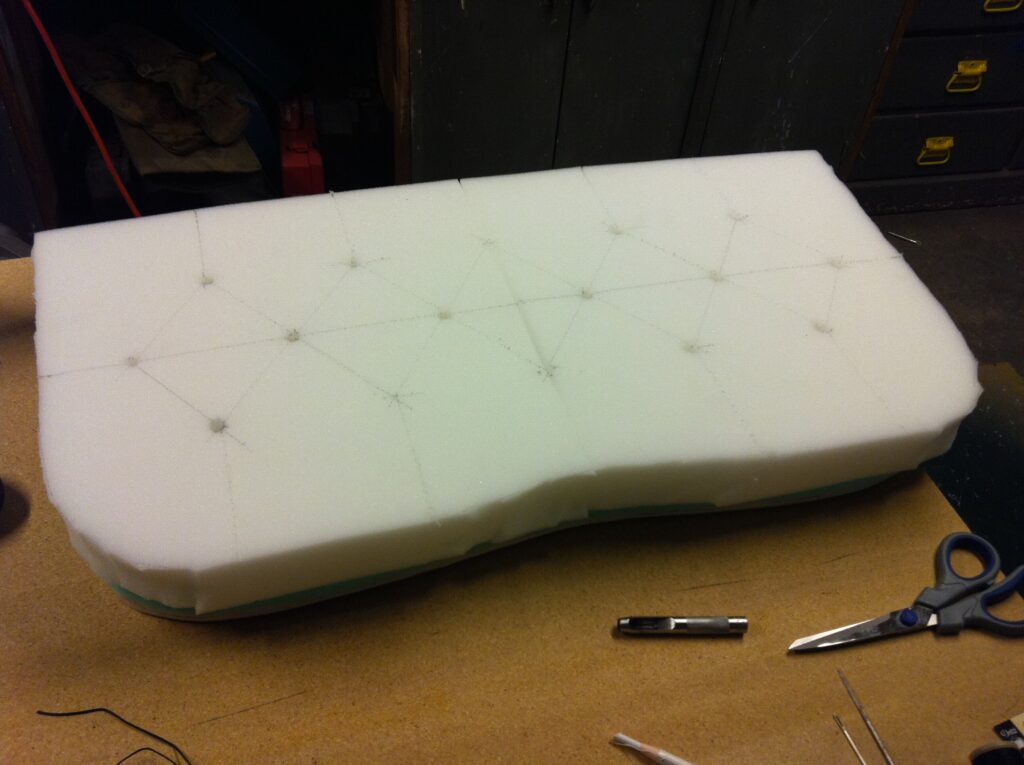

Upholstery begins Padding

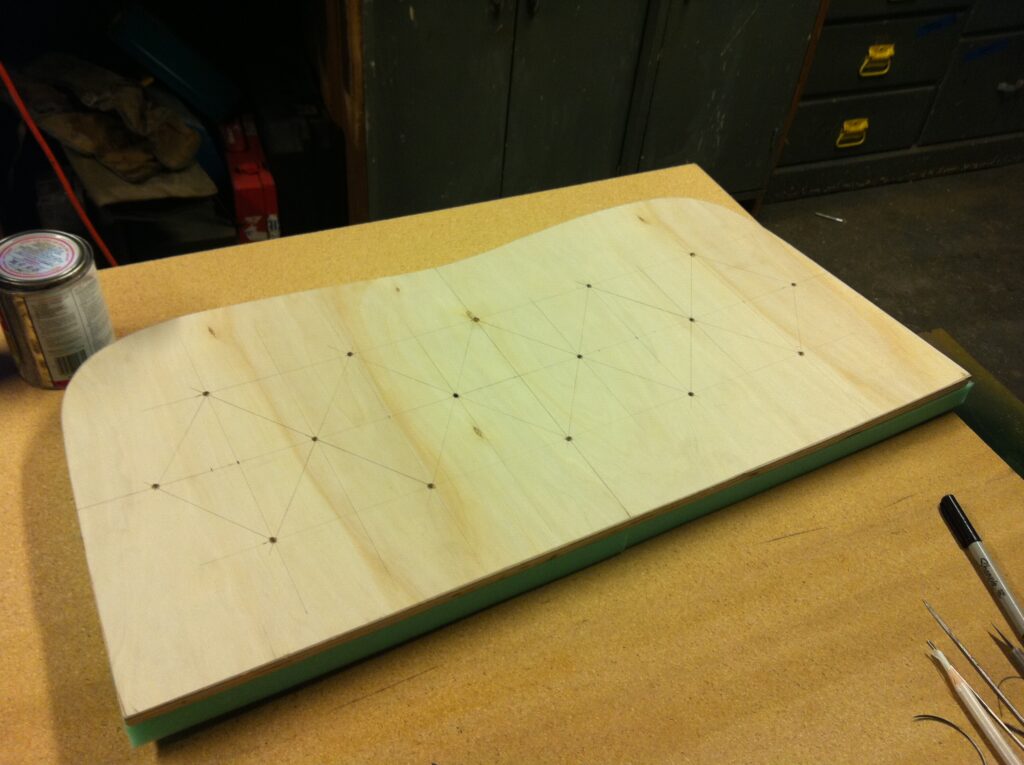

Padding Leather is threaded

Leather is threaded Diamond tufted

Diamond tufted Costumes in work

Costumes in work

Gittreville debut

Gittreville debut inspection

inspection

EVENT GALLERY

Madame and Mademoisell Colignye

Madame and Mademoisell Colignye Dumfries in The Driving Tests

Dumfries in The Driving Tests

Dignified motoring

Dignified motoring unreserved smile!

unreserved smile!

Crossing the Concours award stage

Crossing the Concours award stage Treats

Treats Treats

Treats

Ladies at speed!

Ladies at speed! Tieton

Tieton Tieton Grand Prix

Tieton Grand Prix Mobile soap box

Mobile soap box Campbell Cup

Campbell Cup

ELECTRIC DALLIANCE

Conversion to electric

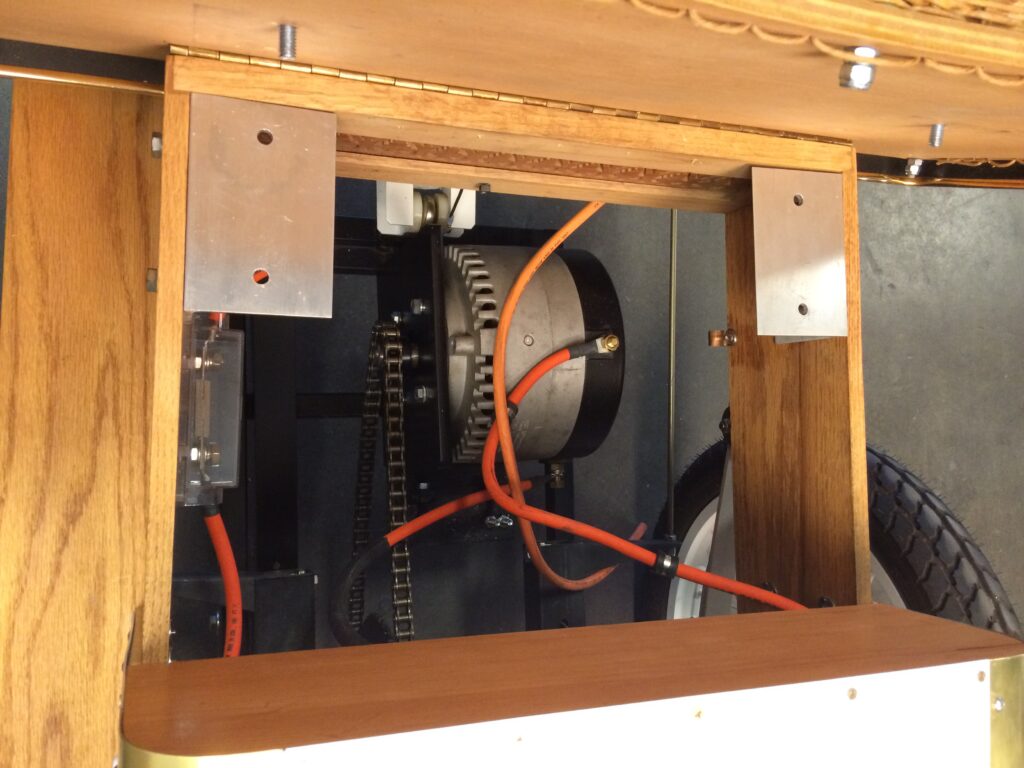

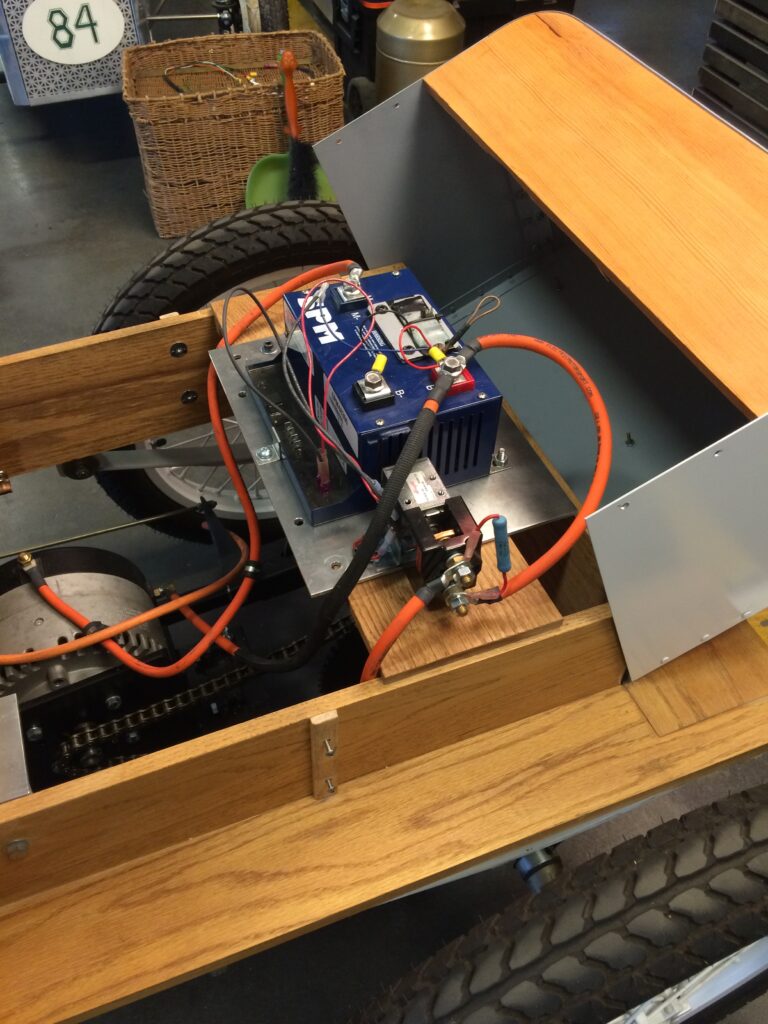

Conversion to electric Motor

Motor Batteries

Batteries Throttle converted to 0-5V

Throttle converted to 0-5V Golfkart controller

Golfkart controller Electric complete

Electric complete

EDWARDIAN GALLERY

Back to gas

Back to gas Snug fit

Snug fit

Stock gas tank but removed from engine

Stock gas tank but removed from engine Civilized electric start

Civilized electric start

Fender fitting

Fender fitting Underside of removable fenders bored for “escape board” use in mud

Underside of removable fenders bored for “escape board” use in mud Ice “sump” installed

Ice “sump” installed

Drain plug

Drain plug

Adventure awaits

Adventure awaits

Afternoon service

Afternoon service

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis No. 1101

Engine: Honda GX 200 Electric start. AGM battery.

Drive: Comet variable drive. #41 chain. 60 tooth driven sprocket. Rear axle is a Peerless differential unit.

Brakes: Two 8” Ø disk brakes. These are controlled by pull rods to a foot pedal on a cross shaft. A hand lever alternately engages the same system. Brakes work very well and predictably even when this heavy car is loaded with a driver and passenger.

Wheels: 17” generic Chinese dirt bike wheels. The dirt bike wheels were selected for their small hubs. The objective was to get as believable an Edwardian look as possible from the wheels. Hubs were modified with a hole saw to get useful bearings into them (NB: not for the faint of heart).

Tires: 3” Michelin Gazelle. The wheel and tire combination would not look out of place in the tile work on Bibendum in London – just as intended.

Front suspension: Semi elliptic. 2’ x 1 1/4” buggy seat springs. Friction dampers. Panhard rod. King pins run in Heim (Rose) joints allowing camber adjustment. U-bolts are welded to the front axle and are in turn bolted to plates on the springs allowing fine caster adjustment.

Steering: Steeply angled steering column acts through an angle gear at a 1:1 ratio. Drag link.

Rear suspension: Semi elliptic (Same spring type as front) with engine sub frame acting as a trailing link (both ends of the rear springs are free). Panhard rod. Provision made for additional coil-over type shock units but these were determined not to be necessary in trials and have ever since been left off.

Brakes: Dual, linked and balance-able, Ø 8″ disks on rear axle. Controllable by foot pedal or hand lever.

Bodywork: Mostly oak. A mix of 3/4” solid oak planks and 1/4” oak plywood. Bonnet is aluminum and brass sheet. Seat back is woven fiber and the seat cushion is diamond tufted leather.

Frame: 0.065” wall, 1.5” round steel tube. Off the shelf (exhaust pipe) mandrel bends were utilized where the frame is curved. This steel frame is significantly stiffened by the oak “bodywork”. It is probably more fair to say that the very rigid wood frame has decorative steel trim attached to it.

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 66.5”, ground clearance: 6” (engine subframe)

Front track: 36.75”, rear track: 35.5”

Overall length: 91”

Width at seat: 30”, radiator width 14.5”

Height: 40.5” (steering wheel), height at scuttle: 31.5”, height at seat: 26”

Weight: 305 lbs (cast iron and brass are heavy!)